By Gary C. Smith and Keith E. Belk, Colorado State University

Legislation was introduced by Democrat Rep. Frank Pallone, Jr., of New Jersey (and several co-sponsors) during the 118th U.S. Congress in April 2023 called the “Food Labeling Modernization Act of 2023” that would modify the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. At the time of submission, the bill was referred to the House Committee on Energy and Commerce, and subsequently to the Subcommittee on Health. Since that time, it does not appear to have moved any further and, given the outcome of recent elections, may not move any further in the foreseeable future.

The Food Labeling Modernization Act of 2023 and Its Implications

Nonetheless, the introduction of the legislation was noteworthy because, if passed, it would require that nutritional information be displayed on the front of food and beverage packaging in a standardized format.

The current form of the bill requires that foods must include on principal display panels a summary of nutritional information using a system that clearly distinguishes between products of greater or lesser nutritional value and that uses standardized symbols to provide information about products that are high in certain substances, such as saturated fats. Labels that use certain terms, such as whole wheat, fruit, or vegetable, must include additional information, such as the amount or quantity of that item in the food. The FDA would be required to develop regulations relating to the use of the terms “natural” or “healthy” on food labels. Requirements for certain foods that contain added coloring, flavoring, phosphorus, caffeine, gluten, allulose, polydextrose, sugar alcohols, or isolated fibers would be included, among other things.1

The FDA’s Evolving Approach to Healthy Food Labeling

In 2022, the FDA updated the Nutrition Facts panel on food/beverage packages to…

- Update Daily Values based on new scientific information

- Require Daily Values for added sugars, vitamin D, and potassium

- No longer require “Calories From Fat” (because research shows that type of fat consumed is more important than the amount) plus vitamins A and C (because deficiencies of these vitamins are rare today)2

The FDA is frantically searching for a definition of the term “Healthy”, and on September 28, 2022 proposed a rule to update the definition of a “Healthy” claim on food packaging that…

- Relies on Dietary Guidelines For Americans (DGFA) and current RDAs of certain nutrients

- Uses a food-group-based approach in addition to “nutrients to limit” (those are saturated fat, sodium, and added sugars)3,4

Dietary Guidelines For Americans (DGFA) Released

The federal government released the 2020-2025 DGFA, dubbed “Make Every Bite Count,” focused on four guidelines (note that the 2025 version of the Guidelines are under development):

- Follow a healthy dietary plan at every stage in life.

- Customize nutrient-dense food and beverage choices for personal preferences, cultural traditions, and available budgets.

- Focus on meeting food group needs (fruits; vegetables; grains; dairy and fortified soy-alternatives; and proteins) and stay within calories.

- Limit foods/beverages higher in added sugars, saturated fat, and sodium.5

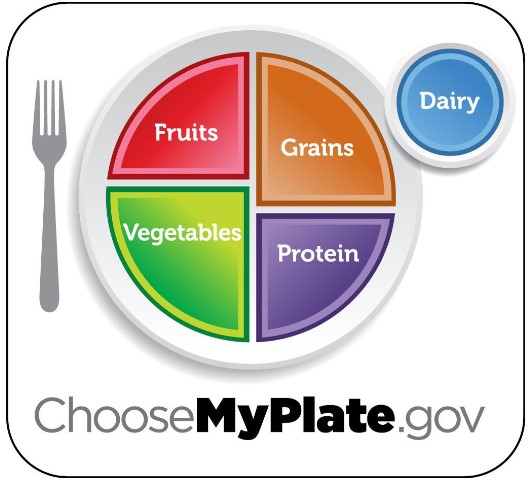

DGFA 2020-2025 redirected its dietary guidance toward food groups and subgroups; redefined the term “nutrient-dense”; doubled-down on “added sugars”; extended its “recommended healthy dietary patterns” to include infants, toddlers, pregnant women, and lactating mothers; and dropped the Food Guide Pyramid in favor of MyPlate.5

“Food Groups” Supplant “Nutrients”

DGFA has shifted its guidance from “nutrients” to “Food Groups” and its recommendations by food groups and subgroups – not specific foods and beverages – to avoid being prescriptive.5,6 It has doubled-down on added sugars saying, “A healthy dietary pattern doesn’t have much room for extra added sugars; foods and beverages high in this component should be limited. Avoid foods and beverages with added sugars for those younger than age two; a small amount can be added to nutrient-dense foods and beverages to help meet food group recommendations.”7

“Nutrient-dense” has been used for decades to describe differences among foods relative to “how much of a food has to be consumed to ingest a given amount of essential nutrients.” DGFA 2020-2025 hijacked the term, defining it as “Nutrient-dense foods provide vitamins, minerals, and other health promotants – and they have no or little added sugars, saturated fat, and sodium.”8

MyPlate Replaces the Food Guide Pyramid

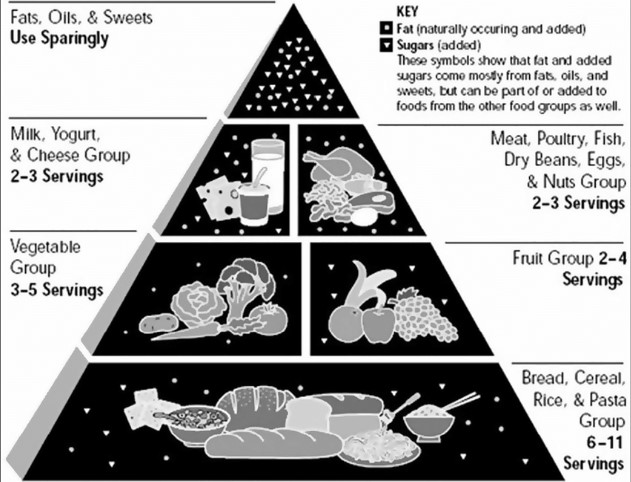

The 2020-2025 DGFA did not contain the USDA Food Guide Pyramid (FGP) and replaced it with an updated diagrammatic depiction called MyPlate. The FGP was created by USDA in support of the DGFAs, became famous, and was the national standard for what all Americans should eat.9 For 29 years , the FGP (referenced as the “Government’s Guide To A Healthful Diet”) was taught to students in public schools and those in the healthcare community with emphasis on a four-tiered “consumer advice” categorization: Eat Less, Eat Moderately, Eat More, Eat Most. Fats, Oils, and Sweets were in the Eat Less tier with an admonition to “Use Sparingly.”10

Dissecting the Food Guide Pyramid and MyPlate

When the six blocks of the FGP are dissected, the DGFA recommends a diet of…

- 41% Bread, Cereal, Rice and Pasta

- 19% Vegetables

- 14% Fruit

- 12% Milk, Yogurt, and Cheese

- 12% Meat, Poultry, Fish, Dry Beans, Eggs, and Nuts

- 2% Fats, Oils, and Sweets11

The diagrammatic depiction of MyPlate consists of a dinner fork, a large circle (a dinner plate), and a small circle (a beverage coaster).7 Placement of names of food groups in the two circles suggests the recommended diet consists of…

- 27% Vegetables

- 27% Grains

- 19% Fruits

- 19% Protein

- 8% Dairy7

For five decades, Big Food has been delighted with the dietary guidance of the AHA, USDA, and FDA: Instead of animal products, we’re supposed to eat plants – they all believe that a nearly vegetarian diet is the healthiest.12

AHA most recently updated its dietary guidance as follows:

- Emphasizing consumption of vegetables, fruits, nuts, legumes, whole grains, lean protein, and fish.

- Suggesting limited intake of foods high in saturated fat and/or cholesterol

- Minimizing consumption of trans fat, sodium, processed meat, refined carbohydrates, and sweetened beverages.13

For more than 40 years, the USDA, FDA, and DGFA have followed in lockstep with AHA dietary guidance,12,14 but all are now transitioning to “food groups” and “eating patterns”, advising consumers to use Nutrition Facts and Ingredient lists to choose individual food products.7,15,16 They’re all sticking with admonitions against saturated fat, added sugars, and sodium but heightening anxiety about refined carbohydrates and ultra-processed foods. This does not bode well for marketers of some food products.

So, going back to what the U.S. Congress asked for with the Food Labeling Modernization Act of 2023, the government has not…

- Identified a standardized format for displaying nutritional information on the front of food packages.

- Created a protocol for distinguishing greater or lesser nutritional value of individual food products

- Decided whether or not to mandate “Warning Symbols” for products high in saturated fat, trans fat, sodium, added sugars, and any other negative nutrients.

- Defined the terms “Healthy” or “Natural”.

That leaves the door open for Big Food to search for a new system to assign relative-ranks for “Healthfulness” to individual food products.

Controversies in Categorizing Foods as “Healthy”

Not everyone believes that categorization of certain foods as “Healthy” and featuring it as a Front-Of-Package (FOP) claim, is a good idea.

An analysis of 1,139 Public Comments sent to the FDA concluded that the majority of respondents favored eliminating the “Healthy” claim altogether.17 In the United Kingdom, use of “Healthy” labels has had essentially no effect on the nutritional values of products sold by the 10 largest food/beverage retailers.18

In a later Public Comment response to the FDA, KrogerTM said, “We support identification of a ‘Healthy’ FOP depiction or symbol but recognize that it will be challenging to distill the many attributes in a food into a single definition.”19

If the criteria for claiming a food product as “Healthy” is decided upon – and deployed by food manufacturers – there will be collateral damage for the implied “Unhealthy” foods.

International Approaches to Front-of-Package Labeling

Since April 2022, food retailers in the United Kingdom have faced severe restrictions as to how they can market “Unhealthy” sugary foods/beverages and snacks.20 Health Canada has mandated use of an FOP symbol as a “Warning Label” on products that contain an amount of saturated fat, sodium, or sugar that is at or above 10% of the applicable Daily Value.21 Health Canada’s Food & Drug Regulations agency intends to restrict “advertising to children” of foods that contribute to excess intakes of sodium, sugars, and saturated fats.22

The FDA has considered using the Food Labeling Modernization Act of 2021 (a previous bill to that of 2023, but similar) to require that a FOP “Warning Symbol” be placed on food products that are high in saturated fat, trans fat, sodium, added sugars, and any other negative nutrients.1 Prognosticators expect the Biden Administration to: (a) raise revenue by taxing “Unhealthy” foods, and (b) issue regulations to limit availability and exposure to junk foods for children especially in the School Lunch Program, and Big Food.23 The FDA has regulatory authority over food labels: the FDA and the Federal Trade Commission have extended their authority to include food advertising (i.e., statements made in flyers, on television, and on the Internet).24 Some of the White House proposals will require Congressional action, while others can be undertaken by the FDA (e.g., FOP nutritional labels, guidelines to reduce sodium and added sugars in foods).25

The Evolution of Health Claims on Food Labels

Prior to 1990, putting a heath claim on a food label was prohibited. Then, because Kellogg’sTM wanted to make claims about diet and health on their cereal boxes, the U.S. Congress passed the NLEA of 1990.26

Since then, the FDA has approved 12 “authorized” and about 30 “qualified” health claims26, and AHA has approved innumerable “Heart Healthy” Checkmarks. All of these can be consumer-facing FOP claims and are intended to attract impulse buyers. Because health claims are dependent on two fluid sets of standards – DGFA ideology and FDA guidance – and the tide is rising, Big Food is searching for an alternative, government-approved system for assessing “Healthfulness” of foods.27,28 It is unclear, exactly who, how, and when a scientist (Dariush Mozaffarian PhD, Tufts University) was hired to invent such a system.

Questioning the Motivation Behind a New Food Guide System

When a food company funds a university to conduct a study, it expects to get results that will favor the company’s product, and they look for one of nutrition’s elite: a university professor who is well-connected at the AHA or NIH.29

One medical professional claims that both Big Pharma and Big Sugar are searching for a lifeline, by..

- Deploying a representative of the Biden Administration (a Dr. Stanley) to claim that obesity is a genetic problem (i.e., if one or both of your parents is obese you have a 50 to 85% chance of becoming obese).

- Funding a bought-and-paid-for academician (a Dr. Mozaffarian) to develop, promote, and lobby for a new Food Guide Pyramid (i.e., the Tufts University, Nutrient Profiling System, Food Compass Scores).30

Others claim that development of the NPS-FCS system was fueled by contributions to Tufts University by Bill Gates (who wants to decimate animal agriculture)27,31 the healthcare sector (that wants a bigger part of national wealth),32 and/or Big Food (e.g., specifically Kellogg’sTM, General MillsTM, and PepsiCoTM who together have more than 100 products ranked by NPS-FCS).33

The Rise of Nutrient Profiling Systems and the Tufts Food Compass Score

Whatever was the case, the National Institutes of Health, apparently under pressure from parts of the food industry, decided to replace the Food Guide Pyramid that was used for years in DGFA.34 What they wanted was to protect high-carb diets, refined carbohydrates, added sugars, and ultra-processed foods; and they wanted a new, government-approved, “identifier” for Front-Of-Package display that would simplify what and how much of certain foods a person should consume.35 Dariush Mozaffarian and his colleagues at Tufts University developed one.36

The Rise of Nutrient Profiling Systems and the Food Compass Score

The Tuft’s University study ranked more than 8,000 foods/beverages by assigning each of them a Nutrient Profiling System, or Food Compass Score (NPS-FCS). The nine nutritional values used to determine “Healthfulness” are…

- Nutrient Ratios – Unsaturated:Saturated Fat; Fiber:Carbohydrate; Potassium:Sodium

- Vitamins

- Minerals

- Food Ingredients

- Additives

- Processing

- Specific Lipids

- Fiber and Protein

- Phytochemicals

Foods with an FCS of 70 to 100 are categorized as “Highly Encouraged, No Limitations”, those with an FCS of 31 to 69 are identified as “Consume In Moderation”; and those with an FCS of 30 or lower are categorized as “Limited Consumption”.36

Since then, a second publication of the same data in the Journal of Nutrition, has added a new “Pyramid Chart” that has three tiers: 70 to 100, “To Be Encouraged”; 31 to 69, “To Be Moderated”, and 30 or lower, “To Be Minimized”.

The food industry will now push for use of the NPS-FCS definition of healthfulness – and especially its new “Pyramid Chart” for Front-Of-Packaging labeling, Warning Labels, taxation, and company ratings.37

Controversies Surrounding the Food Compass Score and Nutritional Rankings

What about those NPS-FCS rankings?

Among 8,023 foods/beverages, only two – watermelon and kale – scored 100. Huh? Watermelon is the most nutritious, most healthful food on the planet? Most people grew up being told that milk, meat, and eggs were the “perfect” foods; they scored 49, 26 and 29, respectively.36 Joe Rogan said, “The rankings were complete, undeniable, indefensible b.s!”31

Here are some more FCS rankings: 70 to 100, Frosted Mini Wheat, almond milk, lettuce, chocolate-covered almonds, Honey Nut Cheerios; 31 to 69, skinless chicken breast, Lucky Charms, Almond M&Ms, potato chips, corn chips; 30 or lower, roast beef, Reese’s Peanut Butter Cup, pork chop, chocolate milk, bacon.36

What do others think of NPS-FCS rankings and categorization?

- Tom Karst says, “FCS ranks fruits and vegetables as almost the only foods that score 70 to 100. I really don’t get it. Lettuce is “healthful” because it contains so much water, but not “nutrient dense” because it contains too much water.”38

- Justin Mares says, “The FCS results are absurd; 70 breakfast cereals (led by Lucky Charms) ranked higher on this new Healthfulness scale than either meat or eggs.”34

- Greg Bloom says, “Sadly, FCS will negatively affect schoolkids, the poor, the sick, and the elderly – the most vulnerable of our communities.29

- Nina Teicholz says, “This is appalling. It ranks Lucky Charms and Cheerios above all meat and dairy products because Dr. Mozaffarian et al. believe saturated fats are bad, and FCS counts added vitamins and minerals.”37

- Tamar Haspel says, “Who’s fault is obesity? 73% of Americans are overweight or obese; the problem is the food system, not the people. Food manufacturers have developed product after product that was deliberately designed to be overeaten.”40

The Future of Front-of-Package Labels and Nutrient Profiling Systems

So far, the government has not acted on any of this,33 but Dariush Mozaffarian is on leave-of-absence from Tufts and is lobbying for adoption of NPS-FCS full-time in Washington DC.14,33

The FDA extended the Comment Period on Draft Guidance for “Questions And Answers About Dietary Guidance Statements In Food Labeling”, but that extension closed on Sept. 25, 2023.41 They issued a presentation of the study titled “Reagan-Udall Foundation Front-of-Package Nutrition Labeling”42 on Nov. 16, 2023. However, the Draft Guidance for “Questions And Answers About Dietary Guidance Statements In Food Labeling” remains listed on FDA’s website in its previous pre-comment 2023 form as of this writing.

On Jan. 14, 2025 the FDA issued a proposal to require at-a-glance nutrition information on the front of packaged foods. We shall see if the proposal gains traction or not in the months ahead.

REFERENCES

- Congress.gov. Accessed December 2, 2024.

- FDA. 2023. usfda@public.govdelivery.com. Accessed on 4/1/2023.

- Demetrakakes, Pan. 2020. Food Processing. April Edition.

- Fusaro, Dave. 2022. Food Processing. October Edition.

- USDA/USDHHS. 2023. DietaryGuidelines.gov. Accessed on 6/29/2023.

- Levy, Sarah. 2018. Food Processing. April Edition.

- USDA. 2023. MyPlate.gov. Accessed on 7/12/2023.

- Gelski, Jeff. 2021. Dairy Processing. November 12 Issue.

- Teicholz, Nina. 2022. Meatingplace. October 28 Issue.

- Eliason, Nat. 2019. Health. April 22 Issue.

- USDA/USDHHS. 2000. Food Guide Pyramid. Washington DC.

- Teicholz, Nina. 2014. The Big Fat Surprise. Simon & Schuster. New York, NY.

- Scott, Chris. 2022. Meatingplace. September 7 Issue.

- Teicholz, Nina. 2023. Unsettled Science. May 25 Issue.

- American Heart Association. 2023. Heart.org. Accessed on 8/17/2023.

- FDA. 2023. EAS Consulting Group. March 29 Issue.

- Levy, Sarah. 2018. Food Processing. April Edition.

- Demetrakakes, Pan. 2021. Food Processing. August 8 Issue.

- Karst, Tom. 2021. The Packer. July 6 Issue.

- Demetrakakes, Pan. 2021. Food Processing. January 4 Issue.

- Health Canada. 2023. Government of Canada. May 16 Issue.

- US Meat Export Federation. 2023. USMEF Export Newsline. May 4 Issue.

- Cardello, Hank. 2020. Hudson Institute. December 2 Issue.

- Steven, S. and E. Presnell. 2022. Food Quality & Safety. May Edition.

- Hoffman, J. and J. Wiesemeyer. 2022. Drovers. September 27 Issue.

- Avis, Ed. 2022. Food Processing. June Edition.

- Carlson, Paige. 2022. Drovers. August 10 Issue.

- Teicholz, Nina. 2021. Nutrition Coalition. November 29 Issue.

- Bekelman, Justin. 2003. Journal of the American Medical Association. 289:454-465.

- Means, Calley. 2023. True-Med®. April 26 Issue.

- Rogan, Joe. 2022. You Tube. Accessed 4//8/2022.

- Makary, Marty. 2023. Fox News. January 10 Issue.

- Teicholz, Nina. 2023. Unsettled Science. February 6 Issue.

- Mares, Justin. 2023. Fox News. January 4 Issue.

- Waters, J. and J. Mares. 2023. Fox News. January 4 Issue.

- Mozaffarian et al. 2021. Nature Food. 2: 809-818.

- Teicholz, Nina. 2021. Nutrition Coalition. November 29 Issue.

- Karst, Tom. 2021. The Packer. November 28 Issue.

- Bloom, Greg. 2022. Meatingplace. September 22 Issue.

- Haspel, Tamar. 2023. The Washington Post. June 29 Issue.

- FDA. 2023. usfda@public.govdelivery.com. Accessed on 6/16/2023.

- FDA. 2023. usfda@public.govdelivery.com. Accessed on 6/30/2023.